6/20/2016. Among my favorite, we enjoyed giving these collected posts on the disappearing black churches of San Francisco’s Western Addition. as a paper at the Vernacular Architecture Forum Conference in Durham, North Carolina in June of 2016 Originally, published in May and June of 2012, they were followed by an afterward on the flipping of the Gethsemane Missionary Baptist in February 2014. We present here chronologically, as written.

LAST OUTPOSTS: BAPTISTS AND A.M.E.’S OF THE WESTERN ADDITION

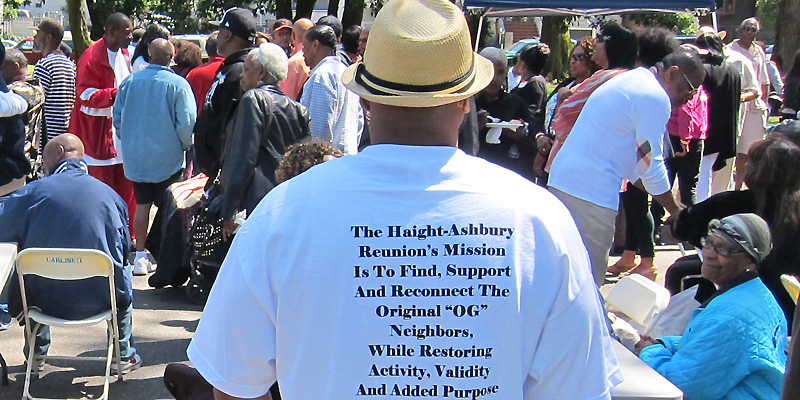

On Thursday evenings and Sundays mornings, the largely white neighborhoods of the Western Addition are transfigured by voices singing the gospel and shouting Amen from within the local African Americans churches of what were predominantly black neighborhoods. Once occupying the entire Western Addition as “the Harlem of the West“, the now scattered black community reassembles in the church choirs and congregations with former neighbors driving in from more affordable neighborhoods across the city, and across the bay for worship and community.

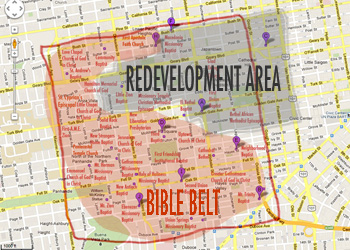

Connecting the dots on a googlemap of “baptist churches”, one can chart the size of the mighty community that filled San Francisco’s Western Addition including the neighborhoods of the Fillmore, both Upper and Lower, Haight Ashbury and the Lower Haight, Hayes Valley, Alamo Square, NoPa and Divisadero Street, the Lower Pacific Heights, Japantown, and Cathedral Hill. Along with the Baptists we’ve added to the map the names of black A.M.E.s (African Methodist Episcopal), C.O.G.I.C.s (Church of God in Christ) and Pentecostals.

The churches range across the heart of the city from the imposing Macedonia Missionary Baptist in Lower Pacific Heights to the gothic Mount Zion Baptist across from Golden Gate Park in the Haight Ashbury, pictured above, and from the rosy Love Chapel Church of God bordering Presidio Heights to the modest Mount Trinity Baptist along the new Octavia Blvd. near Market Street, both shown below.

Over a 69 year history these church communities have fought a continuing battle for permanence and relevance.

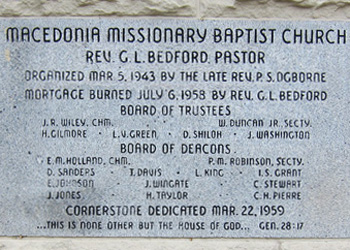

Typical of many, the founder’s plaque at the Macedonia Missionary Baptist dates the Sanctuary’s beginnings to 1943, during the heyday of wartime ship building and at the height of black migration from the deep south. The plaque goes on to proudly honor “Mortgage burned, July 6, 1958,” while one block down, San Francisco Urban Renewal begins its buy-out and wholesale demolition of the district, replacing Geary Street with Geary Boulevard, effectively cleaving Pacific Heights and the Macedonia Missionary from the heavily concentrated black neighborhoods south of Geary with a six lane expressway beginning and ending precisely at the Western Addition borders, serving all but the locals.

Beginning in wartime 1943 like the Macedonia Missionary, the more nomadic congregation of the Greater Gethsemane C.O.G.I.C. suffers both forced and voluntary relocations before settling down. Starting on Eddy Street, ground zero for Urban Renewal Project Area A-1, the congregation relocates to Buchanan Street, soon to become Project Area A-2, where the church is claimed by San Francisco Redevelopment and demolished. Re-established in a former theater in the Lower Haight, they sell to the developer of The Theater Lofts Condominiums. In 1999 Lord Pastor Dad Grant leads his congregation 5 blocks home to the stately 240 Page Street, the former St. Paul’s German Methodist built in 1909, shown below.

Nearby up Page Street, the neon cross at the 2nd Union Baptist still glows nightly after 50 years.

Among the more prominent congregations, the Third Baptist near Alamo Square claims to be the oldest, founded in 1852. Both believers and activists , the church maintains long-standing connections with the N.A.A.C.P. Below W.E.B. Du Bois speaks in the sanctuary to the NAACP in 1958. It has been pastored by the outspoken Dr. Amos C. Brown since 1976, current President of the local branch.

Out at the fringes of the district, two different strategies address the issue of dwindling attendance.

The steeple of the First A.M.E. Zion, the oldest African Methodist Episcopal, congregation west of the Mississippi (1852), stands opposite the private San Francisco Day School at Golden Gate and Masonic, below, one representing the older and one the newer demographic. In 2009, the 26 year old, Rev. Malcolm J. Byrd was called from Brooklyn to re-vitalize the aging congregation. Check out the video of his arrival, “A New Beginning”, for an inside view.

At Turk and Lyon, the congregation of the multi-colored St. Cyprian’s Episcopal, below, adapts to survive, transforming from a 34 member declining black congregation to an integrated neighborhood church, reflecting the evolving neighborhood with significant community outreach programs and its own voice in issues affecting new community interests.

Like the recently publicized foreclosures in Bayview, the steady loss of the churches of the Western Addition through foreclosure, eviction and attrition echoes the economic expulsion and flight of San Francisco’s black population, representing 17% in the 60’s before Urban Renewal and the loss of blue collar work, and now representing 6%. The churches stand as testament of their binding strength as a spiritual homeland for a community dispossessed of its physical, geographical neighborhood.

Above NoPa’s Pentecostal Temple and nearby the recently foreclosed Gethsemane Missionary Baptist.

The next few blog posts present an incomplete catalog of the endangered Western Addition churches, representing both a spirited culture and free-spirited architectural approach. Our interests are:

1. to chronicle the remnants of a disappeared community and an endangered multi-culturalism.

2. to recognize in the simple, evocative forms and iconography of the smaller churches an historical architectural resource that provides a powerful counterpoint to the bric-a-brac laden Victorians in the neighborhoods they renovate.

3. to critique San Francisco’s historical review process that deifies the middle class Victorians, promoting neighborhood consistency while casting out neighborhood diversity and creative affordability.

4 to recognize the negative impact of preservation controls, economic opportunity promotion, and real estate investment on affordable neighborhoods and economically depressed communities.

Below, sidewalk topiary at the Love Chapel Church of God in Christ glows in the light of a setting sun.

Thanks to the recently defunct San Francisco Urban Redevelopment Agency for Geary Street Demolition photo and the San Francisco African American Historical and Cultural Society for DuBois at 3rd Baptist and Joe Philipson for Rev. Amos Brown. And thanks to Mrs. Dominique Jackson Byrd and the First A.M.E. Zion Church for the image of Rev. Malcolm J. Byrd and the video “A New Beginning.” And thanks Michael Raziano for postcard perfect Painted Ladies of San Francisco.

LAST OUTPOSTS: VICTORIANS AND PENTECOSTALS OF THE WESTERN ADDITION

The First Apostolic Faith Church displays a Pentecostal purity of form in stark contrast to the ornament laden Victorians that populate the neighborhood. Cleansed of its Victorian ornament to a powerful austerity and a puritanical severity, the First Apostolic Faith Church at Pierce and Bush, top, provides an affordable and architectural alternative to the prevailing upper middle class styling common in Lower Pacific Heights in Western Addition’s upper end. It represents one of many small and endangered churches still active as its supporting congregation is pushed out of the neighborhood to make way for a less evangelical population.

A Bible belt of small churches, Pentecostals and Baptists, cradles the former Redevelopment Area of the Western Addition. During the reconstruction period of the 1960’s and 70’s the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency replaced demolished Victorian row-houses with large-scale housing blocks. The new plans eliminated small churches, mom and pop corner stores, bars, clubs, even front stoops –all spots for neighborhood socializing. The churches migrated west into the adjacent hospitable Victorian era neighborhoods of Hayes Valley, including the Lower Haight and North of the Panhandle. Shown above, “The indiscriminate mixture of commercial, industrial and residential structures … is the disease of blighted areas.” proclaims the San Francisco Planning Commission in their anti-urban propaganda “New City” of 1947.

Considered Urban Blight by the Redevelopment Agency and now called Painted Ladies, the Victorians of the Western Addition form an astounding collection of which the tour-bus beloved Six Painted Ladies of Alamo Square are but a tiny piece. These other Ladies of a certain age like the one below just happen to be on a different maintenance schedule.

Among the earliest, these classic italianate row houses at Grove and Scott, shown above, represent 10 of more than 1,000 identical homes built throughout Victorian San Francisco by William Hollis’ The Real Estate Associates (TREA), building developer of the early 1870’s with a very successful homeowner package. Between 1870 to 1877, TREA building production averaged 2 to 3 homes a day, a scale of construction, mass production and landscape re-invention comparable to that undertaken by the Redevelopment Agency itself.

Presenting a Before and After view, the Mount Hermon Baptist displays its original Victorian ornament(the Before) on its annex, above left. In contrast, its sanctuary(the After), above right, strips down to a purity of form animated only by subtle use of color, iconography and window placement. Both are Victorian era structures. Both are stunning. The modern sanctuary is also surprising.

In conflict with San Francisco’s legislated Residential Design Guidelines, the Pentecostal Temple at Grove and Lyon and the Second Union Baptist on Page interrupt residential street pattern with positive mid-block socializing and the safety of the bright neon glow–that is as long as the light stays on.

The Solid Rock Church of God re-thinks what Victorian ornamentation can mean. Below the elegant cornice, Victorian trims are removed and replaced with a stone veneer and a tomb like entry. Above the roof peak floats a heavenly cross. Unfortunately, the church’s footing North of the Panhandle seems less than rock solid along with many of the remaining congregations.

The neighborhood churches provide a unique counterpoint in an otherwise well preserved, if less painted, Victorian neighborhood. They up-end our expectations of appropriateness and call to question the restrictive goals of preservation and zoning which encourage greater neighborhood consistency and discourage architectual diversity and affordability at a parcel by parcel scale. If less ornamented than the Victorians, what the small church structures offer the community is variety and character–aesthetic, economic, cultural and certainly spiritual.

Real estate profits, radically improved commercial activity and city infrastructure support the revitalization of the neighborhood but do less to support the fragile economic integration of its community. Historically, the neighborhood was Victorian. Historically, the neighborhood encouraged a middle range of incomes and a diverse community.

Thanks to Eric Fischer for his monumental postings of San Francisco City Planning maps and documents including “Reclaimed from Blight.” Below the crosses of the recently sold Gethsemane Missionary Baptist at Grove and Broderick and the dark cypress at the door of the Emmanuel Church of God in Christ.

LAST OUTPOSTS: LAST DAYS AT GETHSEMANE

“The last days are here.” 80-something, Ray takes his morning constitutional down to the corner store, at Broderick and Fulton around 8 am, hangs out to catch his breath, smoke a cigarette, socialize and sometimes prophesize. We talk about the recent foreclosure and sale of the Gethsemane Missionary Baptist a block away. “I’d been sayin’ it all along, it’s the last days, I do believe that. The last days are here!”

The Gethsemane Missionary Baptist at Grove and Broderick is the latest of Western Addition’s church closures. Neighbor Bill reports the church had been failing for a while and was not shocked to hear the loan had been foreclosed and the property sold. The realtor for sale reports the interior was in shambles.

I bump into Dharma, drinking lattes, a block east at Mojo. He recalls, “I think maybe it was 2004. I ‘member walkin’ by and those walls were like pumpin’.” Here he makes a squeeze-box oompah gesture. “Yeah, it was this cool, loud gospel music. We stuck our heads in, but it didn’t exactly feel right. So ….”

Friday the 13th, April 2012, was the day the music died at Gethsemane Missionary Baptist–the day the foreclosed property was listed for sale.

Friday the 13th, April 2012, was the day the music died at Gethsemane Missionary Baptist–the day the foreclosed property was listed for sale.

As described on the realtor’s website redfin.com: “601 Broderick is a charming old church … in

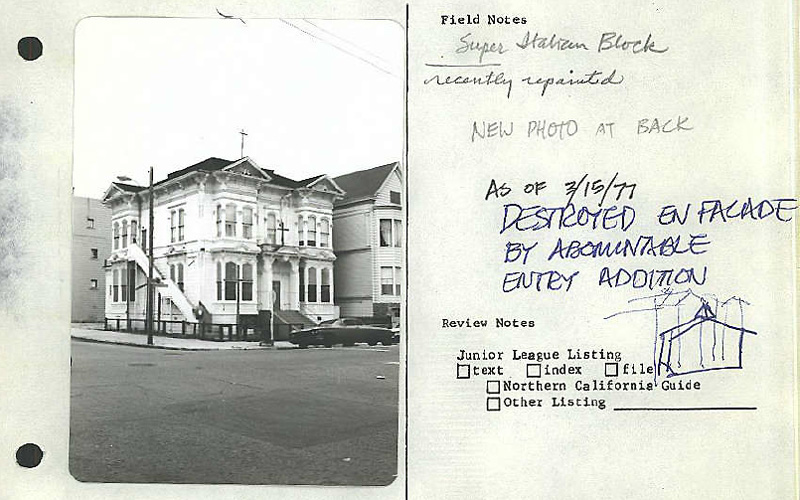

Emphatically squat and unadorned, aluminum windowed and with in-your-face exterior spots, the addition could easily be seen as the Anti-Victorian to an ardent preservationist. The photo from the Planning Department’s 1976 Architectural Field Form shows the original entry porch, intact up to 1976.

“DESTROYED EN FACADE BY ABOMINABLE ENTRY ADDITION.” Overcome with emotion the Planning Department’s Field Notes for 601 Broderick rave with a zealot’s outrage about the 1977 entry addition for the Gethsemane Missionary Baptist. The Field Notes represent the personal indignation and righteousness that mark the beginnings of historical preservation enforcement in San Francisco’s Planning Department.

In 1962 the women’s Junior League of San Francisco, the self-proclaimed incubator for “many of San Francisco’s most successful fundraisers and philanthropists (Opera, Ballet, Symphony, etc.),” initiated a drive-by survey of important historical structures and recorded them in the book Here Today (c 1968). Responding to Western Addition’s decay, Urban Renewal‘s demolition (including 2,500 Victorians) and the post-war craze for asbestos shingle and stucco facade upgrades, the survey focused heavily on homes with Victorian ornamentation. With the advent of Redevelopment Phase 2, their record serves in memoriam the further Victorian disappearances and relocations of the coming decades. Pictured here are Here Today’s authors: Junior League’s Mrs. Alden Crow, the writers Watkins and Olmsted, and the masterful California landscape and architectural photographer Morley Baer.

In 1962 the women’s Junior League of San Francisco, the self-proclaimed incubator for “many of San Francisco’s most successful fundraisers and philanthropists (Opera, Ballet, Symphony, etc.),” initiated a drive-by survey of important historical structures and recorded them in the book Here Today (c 1968). Responding to Western Addition’s decay, Urban Renewal‘s demolition (including 2,500 Victorians) and the post-war craze for asbestos shingle and stucco facade upgrades, the survey focused heavily on homes with Victorian ornamentation. With the advent of Redevelopment Phase 2, their record serves in memoriam the further Victorian disappearances and relocations of the coming decades. Pictured here are Here Today’s authors: Junior League’s Mrs. Alden Crow, the writers Watkins and Olmsted, and the masterful California landscape and architectural photographer Morley Baer.

The volunteer efforts of the Junior League are notable and praiseworthy. Based on their groundbreaking work, the Planning Department extended the list with the 1976 Architectural Survey of rated buildings–10,000 buildings in 60 unpublished volumes, accessible in the department’s database but less available to the general public. For decades this historical listing became the Planning Department’s chief basis for more severe scrutiny of facade alterations comparable to airport security’s no-fly list. With this years online publishing of the survey field forms, the information for all listed properties is at last accessible and its inherent subjectivity evident.

It must be admitted, looking back in time, the historical porch is elegant and charming in the old black-and-white Field Form photograph. And with the loss of the congregation the carefree chutzpah of the 1977 entry addition becomes less supportable to the values and beliefs of a new community. Likewise, its inevitable demolition and architectural loss become trivial compared to the loss of affordable options for a broader community.

The goal of historic preservation remains laudable, but one some can ill afford. In the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s when redlining made home loans unavailable to residents in the Western Addition, maintenance, repair and improvement were not even an option. Today, chipping paint, warped flooring, aluminum windows and asbestos shingles can look as attractively affordable to a budget minded renter or a TIC purchaser, as they can to well-funded developers like the Highland Ferndale Partners.

The goal of historic preservation remains laudable, but one some can ill afford. In the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s when redlining made home loans unavailable to residents in the Western Addition, maintenance, repair and improvement were not even an option. Today, chipping paint, warped flooring, aluminum windows and asbestos shingles can look as attractively affordable to a budget minded renter or a TIC purchaser, as they can to well-funded developers like the Highland Ferndale Partners.

At Gethsemane, one should expect that under the watchful eye and wagging finger of the City’s Historical Review Process a new historical look will be recreated including entry and garage for the freshly painted luxury home at 601 Broderick. And one can reckon that the so-called horrible abomination of an entry that served a rocking congregation for 36 years will be bull-dozed and our post will serve in remembrance.

601 BRODERICK: NOSTALGIA AND AMNESIA

601 Broderick Street at Grove in the heart of NoPa went on the market on October 10th for $5,875,000, 2 1/2 years after the foreclosed black church and fixer-upper was snatched up for 40% above asking at $1,401,000. The open house offered valet service and sushi. Curbed sf’s Tracy Elsen calls it “our absolute favorite flip of the year.”

We featured 601 Broderick in our post Last Days at Gethsemene, noting its place in the origins of historical preservation within the San Francisco Planning Department. Hoodline.com followed up noting provocative neighborhood commentary. For sale on the left: the Gethsemane Missionary Baptist Church in 2012; on right: 601 Broderick restored and re-purposed as a single family home for 2014.

Gentrification has rolled down Divisadero Street through NoPa and Western Addition at such hair-raising velocity that Google bus and $4 toast complaints have become tired cliches of an unstoppable prosperity boom, more so as we befriend new neighbors and clients who enjoy both.  601 Broderick is one of several properties we featured in 2012 that have since flipped to new uses as the vulnerabilities of an established community of fixer uppers are seized by a new community as promising commercial opportunities. The City’s investment has been instrumental in the community transformation through the good intentions of the Great Streets program (Divisadero street beautification), Pavement to Park (parklets), and San Francisco Center for Economic Development (connecting businesses with parcels). The results have created an economic miracle of commercially active street life on the incredibly noisy, congested and traffic challenged Divisadero Corridor, flipping affordability for walk scores.

601 Broderick is one of several properties we featured in 2012 that have since flipped to new uses as the vulnerabilities of an established community of fixer uppers are seized by a new community as promising commercial opportunities. The City’s investment has been instrumental in the community transformation through the good intentions of the Great Streets program (Divisadero street beautification), Pavement to Park (parklets), and San Francisco Center for Economic Development (connecting businesses with parcels). The results have created an economic miracle of commercially active street life on the incredibly noisy, congested and traffic challenged Divisadero Corridor, flipping affordability for walk scores.

Well worth a good thumbing through, the Storied Houses of Alamo Square by longtime Alamo Square resident Joseph Pecora gives us the early history of 601 Broderick. Mr. Abraham Bloch, arrives in San Francisco in 1853 as a gold rush arriviste in clothing retail. In 1886 he invests in his dream home and begins a second career as developer of other properties along the newly constructed Hayes Street cable car line (and future Google bus line) through Western Addition. The home at 601 quickly passes from luxury home to rental income. Pecora notes:

Well worth a good thumbing through, the Storied Houses of Alamo Square by longtime Alamo Square resident Joseph Pecora gives us the early history of 601 Broderick. Mr. Abraham Bloch, arrives in San Francisco in 1853 as a gold rush arriviste in clothing retail. In 1886 he invests in his dream home and begins a second career as developer of other properties along the newly constructed Hayes Street cable car line (and future Google bus line) through Western Addition. The home at 601 quickly passes from luxury home to rental income. Pecora notes:

“By 1910, 601 Broderick’s principal tenant, an enterprising woman named Annie Tuohey, had turned the large dwelling and its rear addition into what by today’s standards would be termed an overpopulated boarding house. According to the federal census of that year, it’s 21 occupants include Mrs. Tuohey, her four children, three in-laws, two boarders, five lodgers and two other households of three persons each.”

From another viewpoint it could be said:

In a pre-Airbnb violation of modern zoning and rental contracts, master-tenant Annie Tuohey takes direct action against the housing crisis and affordability in her fight to survive during the extreme boom and bust cycles afflicting her neighborhood. A working, single mother, she single-handedly creates a workforce incubator and model for co-housing a 100-years hence.

Peeping through windows, the renovated home appears to have great potential for communal living or Airbnb rentals with generous open spaces for living and dining. Speaking from experience, communal living can be fun: on the left hanging with roomies in 1943; on the right, local co-housing 2013; on the very bottom, Scott Street Commune in 1972.

After 50 years of use as affordable rentals the boarding house was purchased in 1953 by the Zion Hill Missionary Baptist Church. In a pact with the devil, the congregation appears to have joined other local African American congregations in receiving assistance from the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency in exchange for their support of Urban Renewal which with bulldozers, wrecking balls and house moving trucks proceeded to rip out the heart of the Fillmore, Geary and Sutter Street neighborhood street scene and social life, demolishing the so-called blight of bars, hang-out corners and jazz clubs of the black community.

After another 60 years as a church with second floor residence, the recent restoration takes us back a century to a 19th Century luxury home. Admired by both neighborhood and City Planning, the meticulous exterior historic restoration reflects the genuine care of the developer David Papale in creating a more attractive neighborhood. It’s lovely work. Stunned by the beautiful transformation, the community suffers a temporary lapse of localized amnesia and conveniently forgets the loss of affordable housing.

Below, the wildly exuberant Victorian entry portico intact in 1959 and more sedate 2014 restoration shortly before initial offering.

Thanks to Elise Hu for her great photo of good living in co-housing in 2014 and David Weisman and Bill Weber for Communal Living “Is this Oz?” from “The Cockettes.” And to Adam Roberts and the Mill for $4 toast, and the Matthew Evans Resource Room at San Francisco State University. Also the provocative, exhaustive, righteous Redevelopment: a Marxist Analysis 1974. And to Kaliflower: the Intercommunal [Free] Newspaper for the Scott Street Commune at 1209 Scott Street photographed shortly before demolition of their affordable housing by the San Francisco Urban Redevelopment Agency.